Languages evolve. I refer here not to the human capacity to engage in linguistic processes, but rather, languages themselves. Actually, languages co-evolve with language capacity, and that is a very interesting topic I studied in grad school with Terry Deacon, David Rudner, and Mark Pagel as mentors and teachers. The point is, though the mechanisms of genetics and utterance are different, languages, like biological systems, are made up of elements that have differing effects, require differing levels of energy to maintain, and therefore, compete or cooperate. Famous smart guy Richard Dawkins provided a tool for discussing some of this in his invention of the term “meme,” a concept I am pretty sure he never fully understood (a genetic determinist can never really get it) but that we all use today. Indeed, “meme” itself is one of the most successful memes, though by chance and not design. Just like evolution.

Anyway, a language evolves, and as it evolves, the various elements of the language change neural systems in the brains of individuals. Even though that is an individual process, there are patterns of change across a culture that engage in and shape that culture’s language. Some of this is easy to see and obvious. Take idiom for example. Certain prepositions have clear material meaning and are unambitious. My computer is on my desk. I can’t arbitrarily say it is under my desk, because it isn’t. No idiom there. But I say I live on 37th Avenue. But I don’t. I live next to* that street. Who lives ON a street? You’d get run over. Meanwhile, my friend Trevor lives in Abbey Road. He gets to live in Abbey road and not on abbey road because he lives in England, where a residence or business or government building is in the street, not on the street. But of course, none of them are ever actually in the street or they’d be run into by cars. These specific idioms are not used by individuals in each of the subcultures referenced here (America and England) by accident. Or should I say on accident. They are used because the linguistic environment in which these words exist potentiate the utility of some words and diminish the utility of other words. In this case, as is generally true with idiom, randomly and arbitrarily. Both words are technically wrong, even misleading, but each is perfectly clear in its respective language context.

Anway (again: sorry I keep digressing) I want to talk about the use of the term “No Kings” in reference to Donald Trump. (A couple of readers may think I wrote this just now because of a conversation we had this morning, March 8th. Not so, I’ve been thinking on this for days!) Donald Trump called himself a “King” the other day, so it makes sense to say “no” to that, right? And yes it does. We don’t want Kings, Trump calls himself a King, so we say, “No way, no Kings, stop that.”

But no, no “No Kings,” please. It is bad framing. Framing is a subfield of linguistic study that recognizes two main things: 1) Meaning is generated in reference to context; and 2) the context-meaning link is hard wired by individual language development into people’s brains. These are closely related concepts.

You are a combat vet, and for a year, every time you heard a loud boom it was someone trying to kill you. You return to Peoria to resume your job as a bank manager, and now you spend a certain amount of time diving under your desk. A car backfires, someone slams a file cabinet shut, or the lid on the dumpster back in the alley closes too fast, all benign events, and you are on the floor. You were not born hard wired to do this, but you are now, at least for a while.

You are a habitual canvasser for Democratic candidates in your area, and every time you knock on the door of a house festooned with American flags and American flag stickers, when it is not the fourth of July, you encounter a MAGA creep. After a while no matter how much you love America, and no matter how patriotic you are, when you see an American flag, you think, “MAGA.” Whenever you do fly the flag yourself, your memory of MAGA comes to the front, and that simple act of patriotism engages a range of responses in your now hardwired brain — hardwired by experience, not at birth — and if you are more honest and less in denial, you recognized that there is conflict in your limbic system. Your personal symbolic-linguistic milieu doesn’t really let you own the flag anymore.

Now consider the word “King” in our culture. It is mostly either positive or funny, or at least neutral. Burger King (have it your way!). King of the Hill (ironic and funny). You get to be King for the day. You are King of your club, you call your friend a King, the best of a set of businesses, things, people, are Kings. We even name our beloved dogs “King” sometimes.

This applies generally to european royalty. The concept of royalty probably emerged well after 10,000 years ago, and appeared across the world in diverse and unconnected cultures during the Holocene, following the concentration of people or wealth, the development of hierarchies of interconnectivity, and the ability to form temporary or standing armies. The Maya and Aztec people, various groups in East Asia, West and southeastern Africa, and the Levant got some kind of monarchy. Eventually it spread into the backwater now known as Europe. The Classical Period Greeks weren’t too into it, but their peer states were, and the Romans had it down to an art. Eventually you get entities resembling the quasi-fictitious King Arthur, and the rest is even more history.

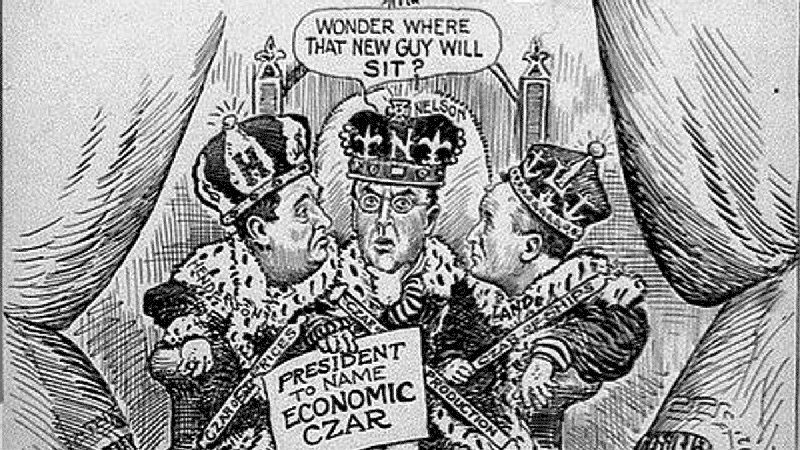

Queen is a positive word in most contexts. Queen for a day. Queen (the band). Queeens (the queens). We even call our dogs some form of the word Queen. And the other royal terms as well. A Czar is a Caesar, a word with a complex history. We might have a negative view of the Russian Czars, but we love the history of Nicholas’ family, we eat Ceasar salad, and when we have a super big-ass problem in America, we find the Greatest of All Time expert on the topic and call them a Czar. Princess and Prince, co-opted by the most significant American arbiter of popular culture, Disney, abound in our stories, and are positive. We name our dogs Prince, Princess, Rex, and Duke, for crying out loud.

But why does a freedom-loving pro-democracy culture love royalty? You might think it is because of the pomp and circumstance, the fanciness of it all, the bright colors or the lurid stories. Somehow our culture, which emerges in uneven part from puritans who eschew materialism, formerly enslaved people, Native cultures (including New World Hispanic) who are more about Seven Generations than amassing power, has on balance culturally hardwired positivity when it comes to royalty. Why?

Evolution. When thinking about evolution, always remember Tinbergen!

Did you forget Tinbergen? Allow me to refresh your memory. Tinbergen set up a system for asking questions about evolution. He laid out four categories of explanation for any given evolutionary trait or phenomenon. I won’t tell you about three of them, that is too much of a digression even for me, but I’ll mention one: Phylogenetic effect. There are a lot of reasons mammals have fur/hair, feed their young via lactation, give live birth, and are homeothermic endotherms (warm blooded). But the reason why any given mammal has these traits is because their parents had these traits. Evolution does not get to redesign from the ground up. If it could, we humans would have wheels and night vision. Traits come down to us with varying degrees of phylogenetic inertia, aka historical drive, and that inertia figures into the mix of what happens next.

Remember Europe and its eventual adoption of royalty? That adoption and long term maintenance of the concept required guard rails and protections. Go back in your Tardis** to 11th century Obodrite and say a lot of bad stuff about the Duke of Saxony. You might lose your head. Go tell a Mayan ruler to get bent. You might lose your heart. Go to ancient Yangzhou and say something bad about Emperor Han Wendi and you might lose a foot. Maybe not say anything bad about royalty. Maybe only praise royalty. God save the King! Long live the King! We really like you guys, leave us alone!

I’m sure it is not all negative reinforcement. Royalty has may ways of convincing its subjects to love it. That includes the pomp, the strength, the protective framework.

Please do not confuse the evolution of a language and a culture with organic genetic evolution. I’m not making that link here, please you don’t as well. Since Aristotle and before (but he was the first one to write it down) we’ve known that a language (or, commonly, a language family or set of languages) can have themes that link our systems of memory, our limbic responses (emotions), and our overall meaning generation to the words we use, and visa versa. Put more simply, the neural structures in our brain that have to do with our system of communication are shaped by the linguistic environment we grow up in, so if you want to communicate effectively, you need to reckon with the way the words you utter fiddle with the neurons in your audience’s brains. It does not matter what you think. It matters how their brains react.

We know that a lot of this happens within the language system itself and not the biological property of having language capacity, because the themes of rhetoric or meaning making are often linked to language conventions that vary wildly across language families. There are jokes you can make in KiSwahili that you can’t make in English, and references to truthiness that are easily added to a conversation in Quechua that would require paragraphs in German.

This essay is a long way of saying two things, one esoteric and academic, the other pragmatic and that as a political activist you need to know now:

European language systems generally, including all modern English speaking systems such as American English, link words for royalty to positive features of society because for a very long time, centuries and centuries, all of the languages related to the evolution of modern English (including Latin, early French, early German, etc.) existed in a culture where it was required on pain of death or torture to speak well of royal things, or was positively reinforced by other mechanisms.

No matter how much you as a democracy and freedom loving American dislike the idea of royalty on principle, if you use words generally linked to royalty, such as “king” in your messaging, you will be firing positive neurons in the brains of the people you are communicating with. Don’t say “No Kings” when speaking of Trump. Maybe say “no dictators,” “no tyrants,” “no fascists,” or “no despots.”

This is a slight departure from what I usually hear my fellow messaging mavens say. They say to avoid words like “king” because it imparts strength, and polling shows that Americans like strong leaders. That is certainly true, but I think what I’m saying here is also true. On balance our brains are mostly pro-royalty whether we like it or not. Note that the terms “tyrant” and “fascist” did have their day, the former in ancient Greece, the latter in the early 20th century. They were good words linked to strength, and at least “fascist” was a populist term linked to positive change. That all went pear shaped during and after World War II, and the term “fascist” went from good to bad. Note that this term has a shallow history, emerging in the 19th century, and a narrow range, being used primarily in Italy at first. “Fascist” never had a chance to earn a place in our neuro-language system and is a pale blip compared to King and Czar/Caesar, or Prince, Princess and even Duke.

Titles of nobility linked to deeper time and a broader landscape tend to be more noble. Huh.

Footnotes:

*Technically that is a postposition, not a preposition.

**Time machine.

I did that while writing the post, but there is a back arrow undo thingie in the main editor.

I hate this. I had a long, thoughtful comment in reply, and accidentally backspaced and lost it all. And I don't have time to retype it.

Trust me, it was profound.